Why I am so Nuts about Family History? – Part One

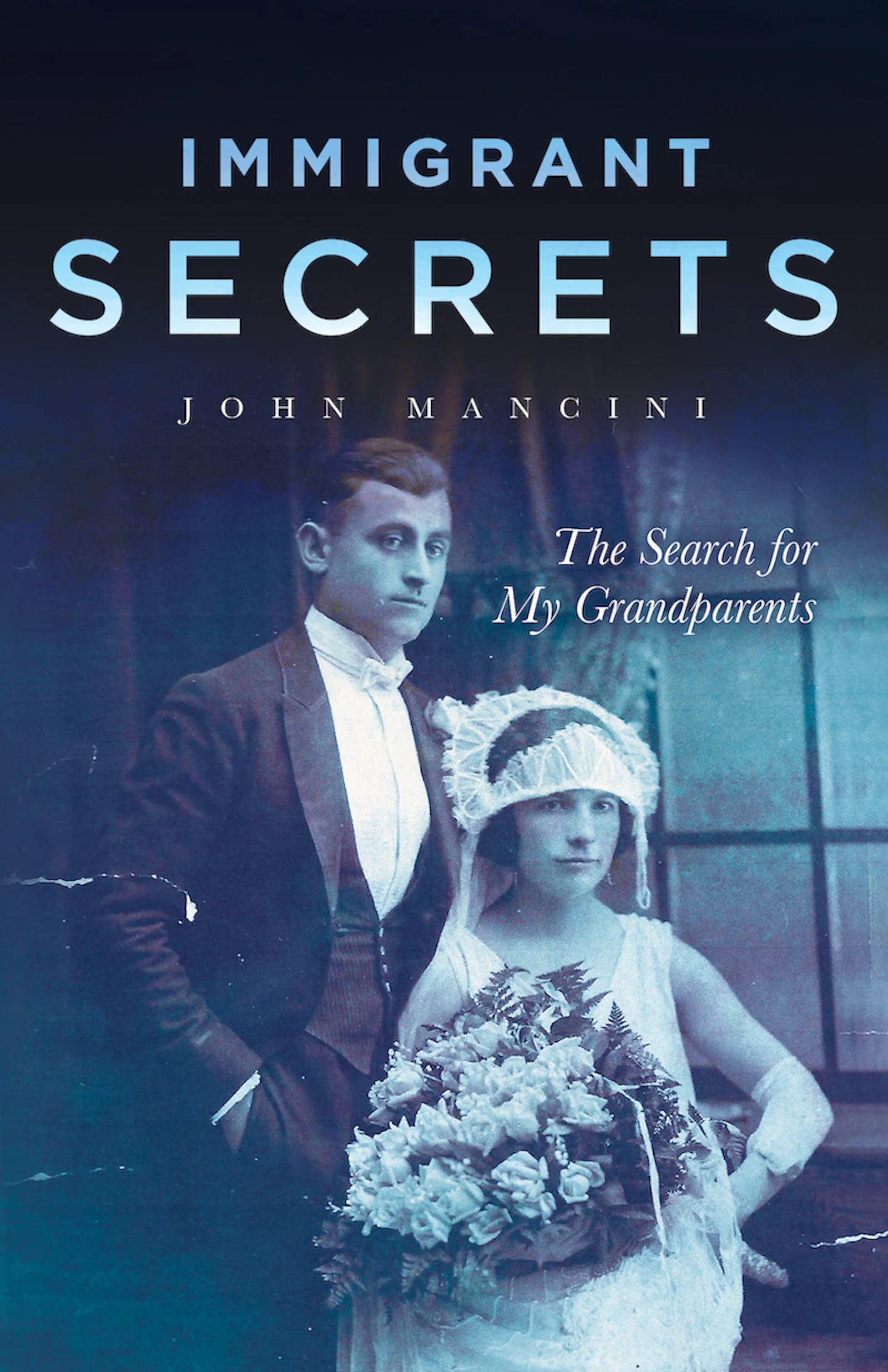

Over the course of the last five years or so, I spent an inordinate amount of time try to figure out the mystery of my missing immigrant grandparents who died in the 1930s – except they didn’t -- and why my father never said anything – anything – about his family. The research ultimately culminated in a book, Immigrant Secrets.

Along the way, I’ve run into some people mystified by my preoccupation with finding out what happened to my grandparents. Some comments have been of the “You should let sleeping dogs lie” vein. Others asked in various forms, “Why would you even want to know?” Still others wondered, “And you think this story is important because…..”

These are all fair questions. I will admit that initially, my obsession was somewhat driven by mere curiosity. I suppose some of this was prompted by the shortness of my own family line – which pretty much stopped with my four immigrant grandparents (two Italian, one Irish, one either Swedish or Australian – but that’s a mystery for another day).

This was in direct contrast to my wife’s impressive Revolutionary War pedigree. I can still hear my mother-in-law’s sweet voice, “My mother was a Stull, her mother was a Davis, her mother was Baylor, her mother was a Glen, and her mother was an Abernathy — and they fought in the Revolutionary War.” I was amazed at this, and doubly amazed at the thought that my mother in law’s life overlapped for eight years with that of a grandfather who fought in the Civil War for four years and survived Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. My American history major mind reeled at the direction connection back to the Civil War.

Perhaps another element was simply the ticking clock. In the summer of 2017, I realized that I had lived one day longer than the 22,834 days accorded to my father and that I was officially in uncharted territory. The statute of limitations on being your father’s son never quite runs out, but it certainly takes on a different feel once you live longer than he did.

And I guess the most important element was becoming a grandparent, which highlighted not only the missing grandparents in my own story, but also the long links we each have in our own family chains, looking both backwards and forwards in time. Without any memory of them, in some way did my father’s parents even exist? If their lives went unrecorded and forgotten — what then? What did it mean to my father to have this void in his life? What did it mean to us to be missing half our family? We didn’t know anything about them other than their names and a few very sketchy details. What did it mean to have no ancestors on his side to honor or remember?

This question of the unexpected arc of each of our stories has been particularly on my mind as first I watched the waves of refugees overwhelming the U.S. southern border, and now I watch the exodus from the Ukraine. Most religions have a narrative describing how strangers should be treated. Unfortunately, most countries – and for that matter most of us individually -- come up short when it comes to putting those beliefs into action. Those few that put those beliefs into action create an arc of simple kindness that can transform all of us if we let them.

But it is the longer arc of each of these immigrant and refugee stories that I find the most overwhelming. Without providing a spoiler for those who may wish to read about my grandparents’ story, by any short-term rational calculation those inspectors roaming the queues in the Great Hall at Ellis Island in 1921 when my grandparents arrived should have turned them away. When I hear some of the recent harsh voices making judgment on the potential burden of those seeking better lives, I cannot help but think that those voices would have likely been the first to send Francesco and Elisabetta packing. And sadly, they would have been justified, at least in the harsh cost-benefit of short-term decisions. Their lives were a waste, and they would prove to be a burden on New York State for most of their lives.

And yet, there was a longer arc to their sad lives, an arc that purely rational calculations in 1921 could not have imagined, but an arc that I think genealogists will appreciate:

• 2 sons.

• 9 grandchildren.

• 21 great grandchildren.

• 17 great-great grandchildren.