What do we think about ancestors who fought on the wrong side?

I recently finished Endpapers, by Alexander Wolff. As readers of Immigrant Secrets know, I’m a bit preoccupied with the mystery story of my own grandparents, so the premise of Wolff’s book immediately grabbed my attention:

I spent a year in Berlin exploring the lives of my grandfather and father—Kurt Wolff, dubbed “perhaps the twentieth century’s most discriminating publisher” by the New York Times Book Review, and his son Niko, who fought in the Wehrmacht during World War II before coming to America. Endpapers tells of the journeys of these two German-born men turned American citizens, and my own quest to make sense of their stories amidst rising rightist populism on both sides of the Atlantic.

The book is terrific on so many fronts. It’s an origins story, an exploration of family relationships, an early 20th century European history, a profile of the publishing industry, an analysis of anti-Semitism, and a dive into the roots of Fascism, just to name a few. I spent a number of years just trying to find a few scattered data points about my grandparents’ lives, and will admit to an enormous amount of jealousy for the depth and abundance of Wolff’s sources. For anyone doing family history research, you will be astonished at the abundance of resources and archives about his family, and how he has woven this abundance into a great story.

The story of Wolff’s father Niko’s service as a Wehrmacht officer on the Russian front during World War 2 kept poking me to do a dive into a fellow on my wife’s side, Caleb Sowers, pictured here with my late mother-in-law, mostly likely around 1922.

I’ve always been intrigued by the stories from my wife’s side of our family. First, because she actually had stories — she knows ancestors dating back before the Revolutionary War — whereas I was initially lacking in any stories beyond my grandparents (and as Immigrant Secrets readers know, even that statement is a bit of a stretch). My wife’s great grandfather, Caleb Sowers, served in the 24th Virginia Infantry (the Floyd Riflemen) for almost the entire U.S. Civil War. He enlisted shortly after the Civil War began, and served until just a few days before the surrender at Appomattox — he was captured at a crossroads battle outside of Petersburg called Five Forks (there is still an exit off I-85 for Five Forks). He was a drummer, and was in a number of notable battles, most notably Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg.

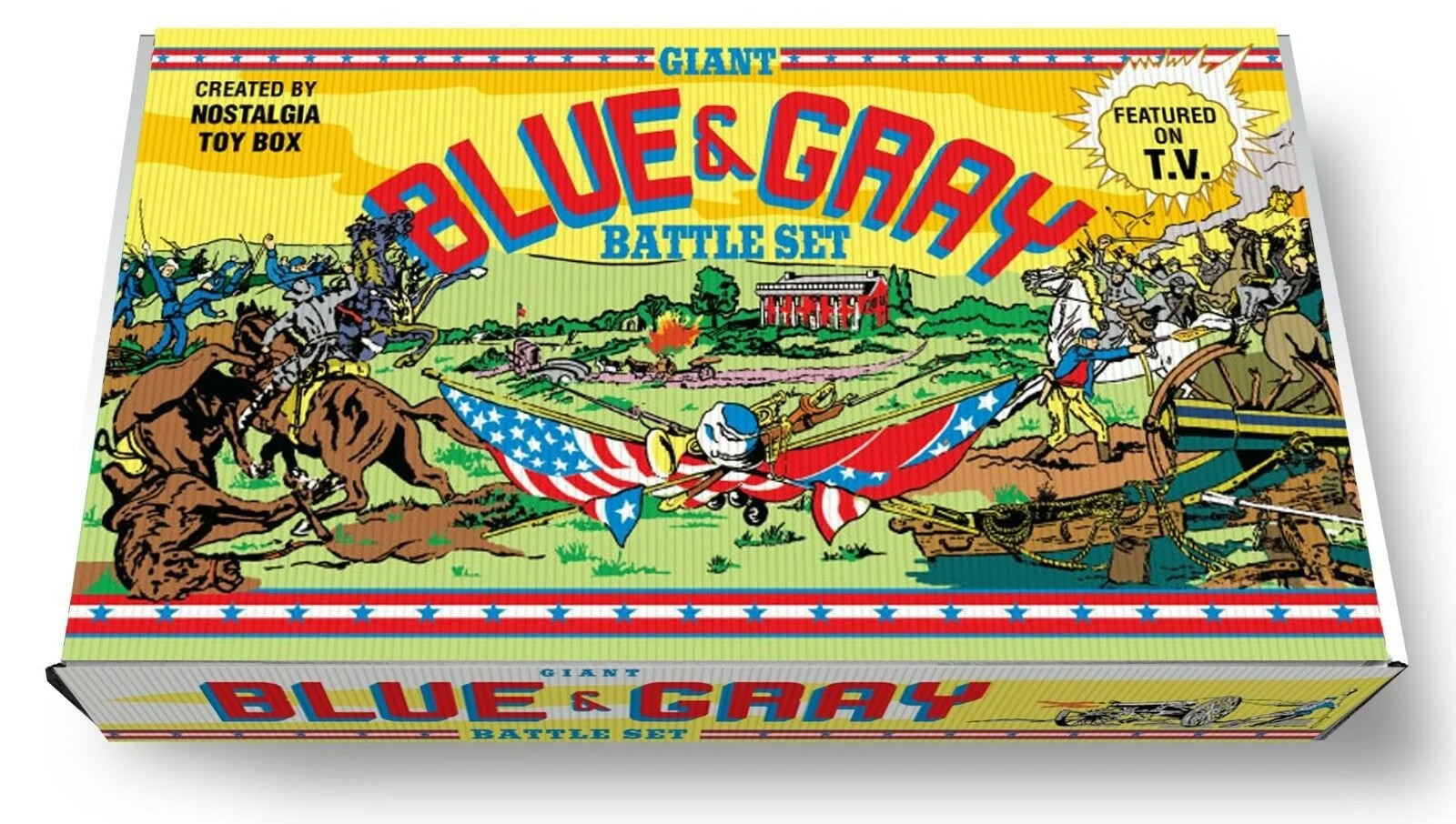

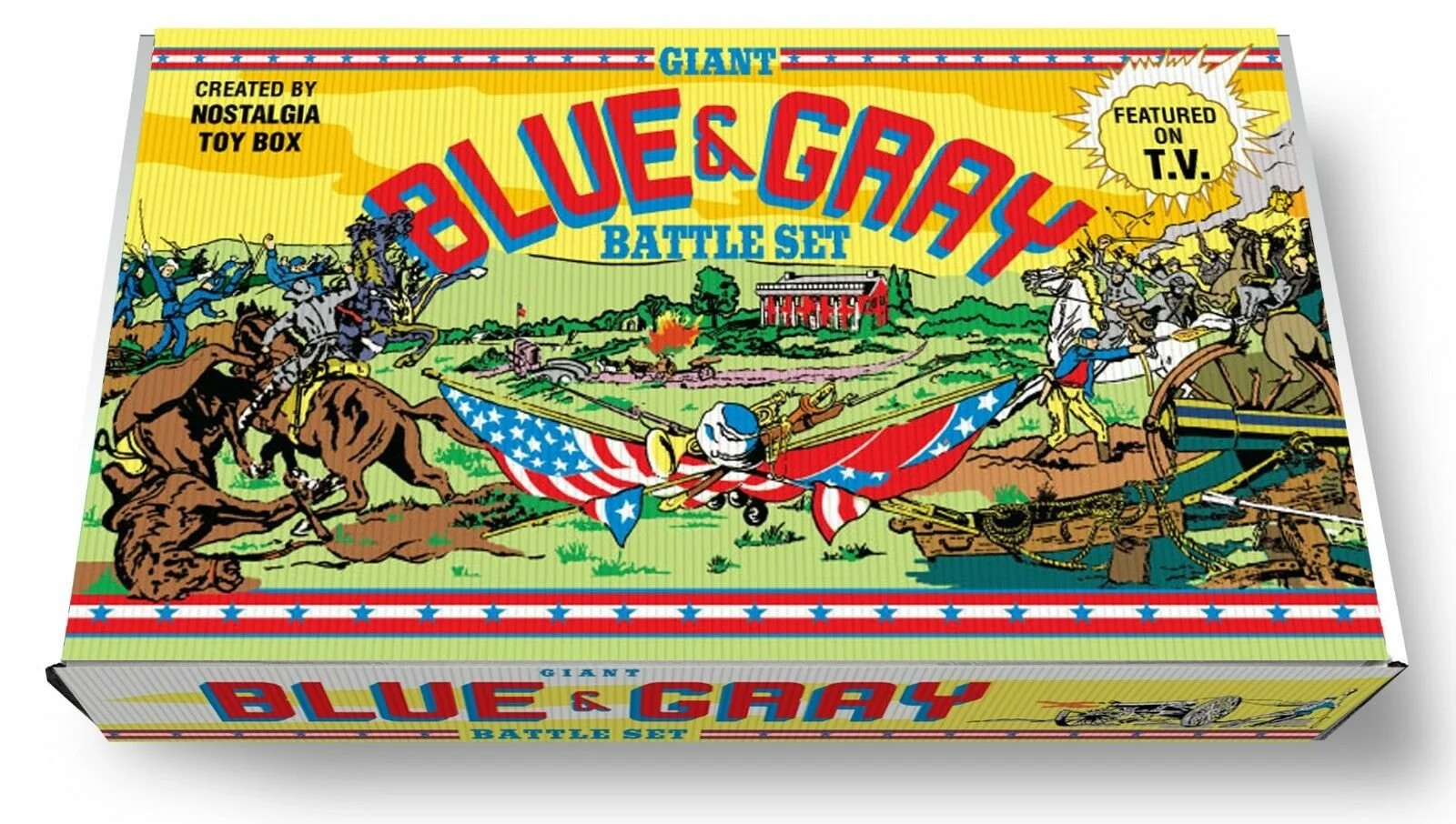

The other reason that I’ve always been interested in Caleb is that I have had a long-time interest in the Civil War going back to my childhood. At some early age, I got the Marx Giant Battle of the Blue and Gray Toy set, and my brother Joe and I would stage countless battles, usually utilizing these soldiers in a battle featuring Lincoln Log catapults (using the roofing strips and end pieces). As time went on, we added card houses made out of early 1960s baseball cards to the battles — thereby ruining their future value as a source of retirement funds.

Of course, as the older brother I usually made my brother Joe be in charge of the Confederates — the losing side — while I took charge of the blue guys, little realizing the history of the family that I would eventually marry into. And for a long time, that’s really the frame for how I looked at the Civil War — one side lost, and another won — and viewed the stories surrounding individuals on each side as just that — stories about individuals in war.

But as I’ve thought about this over the last decade, the Civil War represents not just a case of one side won and the other lost. In the long arc of history, it’s just not that simple. And reading Wolff’s book, I kept coming back to the same question, a question that I think I need to pose up front before proceeding to document Caleb’s history. However, I am having a difficult time admitting to the question I really want to raise. Niko fought for the Nazis, and Caleb fought for the Confederacy, and service for either has a far deeper connotation to modern ears than an ancestor who served, say, on the French side in the Franco-Prussian War.

What does it mean to have an ancestor who fought on the wrong side in a war?

Honestly, this makes me a bit reluctant to begin this project. Clearly, we would view an ancestor who was a political leader in the Confederacy and a defender of slavery with embarrassment and horror, as we would an ancestor who was a senior Nazi official. And this is the context in which I tend to view a lot of the conversations about statues of Confederate leaders and generals all over the South erected in the Jim Crow era.

But what about average people like Nico and Caleb, people who were drafted or volunteered into service on behalf of not just the losing side, but on behalf of the wrong side? What are we to think about them? History is ultimately written by the winners, but it is not confined to them. We tend to conflate the cause people served with how we feel about their own service. Certainly not every soldier who served on the Allied side in World War 2 behaved in a way that we would consider heroic, nor was every German or Japanese soldier a villain.

I suppose one of the reasons that All Quiet on the Western Front so engaged me when I was in high school — yes, this does happen, even thought we would have been loathe to admit it at the time — was the fact that it was written from the perspective of a German soldier. The author notes in the beginning of the book,

This book is to be neither an accusation nor a confession, and least of all an adventure, for death is not an adventure to those who stand face to face with it. It will try simply to tell of a generation of men who, even though they may have escaped shells, were destroyed by the war.

Another issue that bothers me is our tendency to apply contemporary standards to behaviors that occurred 50, 100, or 150 years ago. I suppose that makes us feel self-righteous, but I think denying the context in which history occurred creates an overly simplified cast of heroes and villains. Humans can rise above their contemporary context, but their actions occur within that context. And ultimately, if we believe in such a thing as progress, how people act in the context of the time in which they live matters.

President Obama frequently quoted Dr. King about the “long arc of the moral universe.”

Evil may so shape events that Caesar will occupy a palace and Christ a cross, but that same Christ will rise up and split history into A.D. and B.C., so that even the life of Caesar must be dated by his name. Yes, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

So I think as I explore Caleb’s history, my objective is not to glorify it, and certainly not to glorify the cause he served. Rather, I think I want to document it and understand it, not celebrate it, keeping in mind that his actions were on the wrong side of history.

Yes, these posts are going to be a bit complicated.