How will future genealogists know what is truth?

Diogenes Searching for an Honest Man (1640–1647) by Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione held at the National Gallery of Art

Note: A version of this article originally appeared on my MER Merlin Perspectives blog.

Diogenes of Sinope is best known for his search for an honest man — and for truth.

He was most likely a student of the philosopher Antisthenes and, in the words of Plato (allegedly), was “A Socrates gone mad.” He was driven into exile from his native city of Sinope for defacing currency (though some sources say it was his father who committed the crime and Diogenes simply followed him into exile). He made a home for himself in Athens in the agora, living in a rain barrel and surviving off gifts from admirers, foraging, and begging….By holding a literal light up to people's faces in broad daylight, he forced them to recognize their participation in practices that prevented them from living truthfully. [Source: WorldHistory.org]

Having never taken a philosophy course in college, it is perhaps a bit cheeky of me to opine on the nature of truth. Given this gap in my education, I will resort to the source of all modern truth -- Wikipedia -- to find a working definition of truth. Even though the Wikipedia article on truth is far too complex and long for me (I nodded off at the section on the “Correspondence Theory of Truth”), I did manage to jot down the first sentence: “Truth is the property of being in accord with fact or reality.”

President John Adams once said, “Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence." In the modern era, though, I’m concerned that “being in accord with fact or reality” ain’t what it used to be. And I’m not sure how we will find our way back.

One of the things that I respect most about genealogists who are serious about their craft is their insistence on documentation of their findings. For the most part, we have always assumed that the primary raw materials genealogists use to document their findings — official documents, images, old correspondence, and newspaper articles — are “real.” These sources may not always prove 100% accurate, but we normally err on the side of assuming that they are at least a good faith effort to capture a moment or person in our past.

I am not sure that this will be the case for future generations of genealogists, who will struggle with how much to trust contemporary sources.

This is especially problematic in the era of user-contributed content on Ancestry.com. It is amazing how a simple well-intentioned but error-laden contribution can multiply and multiple and multiply across multiple family trees. Facts can be stubborn things, but so too can mistakes repeated often enough. How this all gets unravelled now that the user-contributed content cat is out of the bag is a tough question.

It is said that a picture is worth a thousand words, and as a result, our default assumption about the images that we rely upon for information about our ancestors is that they may not always be pretty, but they are at least “real.” We’ve always been a society that places a high value on visual evidence. “Just show me the document.” “Show me the picture.” “I want to see the video.” But what happens if these traditional indicators of “truth” can no longer be trusted? Determining what is real and what is fake is increasingly difficult, if not impossible for the average person. In the future, who knows? The infinite number of filters we can apply to any image and ubiquitous photo editing tools raise questions — or they should — about the reality of any image. This does not even begin to address the complexities raised for future generations of genealogists about images created with the Google Pixel 6 that utilize the Magic Eraser to just eliminate the awkward Uncle Henry from that family photo.

In terms of “news,” something has changed in the era of social media. We have morphed into a society that increasingly chooses what to believe rather than discerning what is factual. It is no longer necessary to have facts; very passionate positions on a host of issues are now determined by “something I heard from a guy on the internet.” Kurt Andersen’s Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire is a bit over the top for me in some places, but he hits the core problem of modern “truth” head on:

The American experiment, the original embodiment of the great Enlightenment idea of intellectual freedom, every individual free to believe anything she wishes, has metastasized out of control….We have passed through the looking glass and down the rabbit hole. America has mutated into Fantasyland. [Andersen, Kurt. Fantasyland (p. 5 and 6). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition].

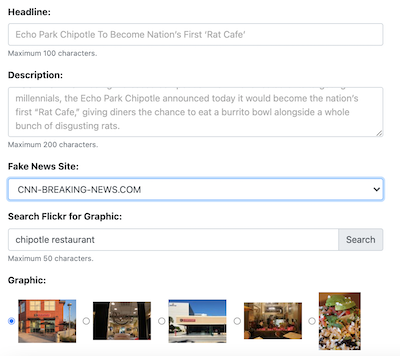

At the simplest level, a clickable piece of fake news, attributable to a news organization, is available in less than 10 seconds with a few entries (I won’t provide the URL to this site here — there is no need to encourage even more fake news.) Here’s the form….

And the output…

Voila! Is it identifiable as a fake, yes. Could it be distributed around world millions of times before the creator is called on it? You betcha.

Fake videos are particularly problematic (Reimagining Information Authenticity). To illustrate how the scale of the problem multiplies as previously expensive and complicated technologies are consumerized, I did a search on “fake video.” Here are just a few of the search results…

Tom Cruise Test Shows People Can’t Detect Fake Videos Even When They Know They Are Fake

Truth or Fake - Fake videos using robotic voices and deepfakes circulate in Mali

No, this isn't footage of China launching a fake sun into space

Watch: Delhi Police warns of fake video to create discord in Sikh community

I send myself drinks from fake secret admirers on first dates so they know I'm in demand

And on and on the list goes…

What will all this mean to future generations of family historians?

I’d welcome thoughts and comments on how those in the genealogy, records, and archives biz think we should start future-proofing the documents, news, and pictures that are so critical to accurately remembering the past.

John Mancini is the author of IMMIGRANT SECRETS, the story of how he unraveled the mystery of his lost grandparents.