Genealogists Unite! - Release the Records

The only thing my father ever said about his Italian immigrant family was that his parents died in the 1930s, shortly after arriving at Ellis Island.

Once I began the search for my grandparents, I was able to quickly identify a core set of facts about them. My grandmother came to the US in 1920 about the R.M.S. Olympic, the sister ship of the Titanic. Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., and Mary Pickford were on the same voyage – albeit in a very different class of travel – and were returning from their honeymoon. A marriage record from the now defunct Mary Help of Christians Church, provided with the help of a very kind church archivist, gave me their birth dates and hometown. Itri, Italy -- along the Appian Way between Naples and Rome. The 1925 New York State Census and the 1930 U.S. Census revealed that they lived in lower Manhattan near the Flatiron Building, with my grandfather initially employed as a corset cutter and then opening a fruit and vegetable stand with his brother.

Armed with these cursory facts, and confident in my archive-hunting skills, I turned from there to discover how my grandparents died.

I then ran into countless dead-ends. I thought there might have been a mention of the deaths of my grandparents in a newspaper, especially if they died at the same time. My sister and I recalled mention of a fire in the skeletal family origins conversations we had, although none of my other siblings had any memory of this alleged fire. Nothing turned up. I tried to find death certificates, but again, all dead ends. After the 1930 Census, my grandparents simply seemed to have disappeared.

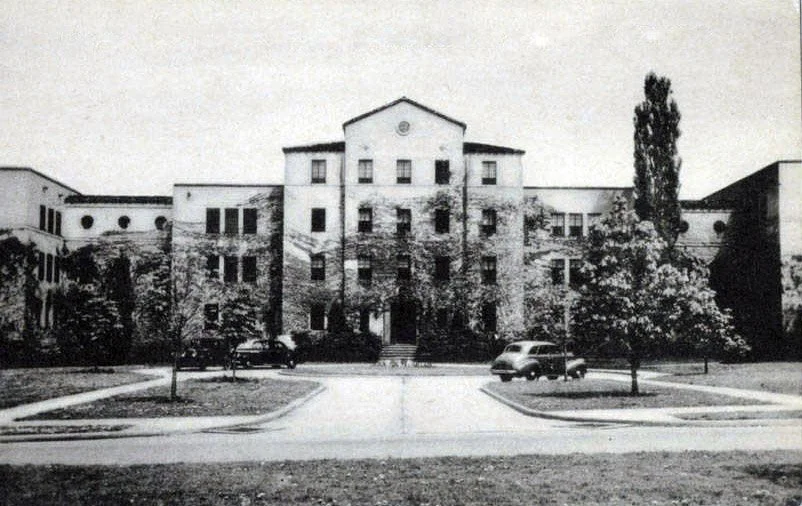

Rockland Asylum

Until the 1940 U.S. Census. And then my “dead” grandparents magically appeared, but as inmates at the Rockland Insane Asylum.

So many questions. What happened? Why all the secrecy? How did they wind up in the asylum in 1940? And what happened to them after that?

I initially tried to request their records from various NY state agencies, thinking this would not be difficult since I was the nearest living relative of my grandparents. I did so both directly and through Freedom of Information Act requests but ran into brick wall after brick wall. The refrain was always the same. Per the New York State Office of Mental Health, if you are a family member of a deceased patient, you can request information if:

You have proof of the patient’s permission prior to his/her death.

It is relevant to your own health and is requested by your physician.

You are the executor of the estate and have included a copy of court papers.

Have written consent from the executor.

Which, of course, means that for the most part, no one who cares about these records can actually access them. Along this journey, I ran into countless tragic stories of other people whose deceased relatives had been institutionalized long ago in the New York Mental Health system and had been systematically denied any information about what had happened to them. All in the name of a misguided and antiquated concept of privacy.

At this point, I was near to giving up the search; there didn’t seem to be anywhere else to turn. And then I got lucky.

I came across a terrific book, Annie’s Ghosts by Washington Post editor Steve Luxenberg. In it he describes his somewhat similar and frustrating journey across the psychiatric commitment records landscape. When his mother died, Luxenberg discovered he’d had an aunt, unknown and warehoused for many years in a Detroit mental hospital. Steve suggested that I go down the path of finding the original commitment papers. He told me that legal documents have a different set of privacy restrictions associated with them than do health documents.

This led me via a circuitous route eventually to the New York Supreme Court Records Reading Room on Centre Street, a location straight out of a movie set. Once I got there, I got two accordion folders, one for my grandfather’s 1932 commitment, and another one for my grandmother’s 1938 commitment. The 1932 file told me the sad story of what had happened to him. Strangely though, the 1938 record for my grandmother was marked “sealed by the court.”

After talking to several people in the Records Room, the consensus was that I would need an actual court order to open this record. As I was preparing to figure out this process, COVID hit, and everything came to a grinding halt. In the middle of COVID, I determined that there was in fact a 75-year statute of limitations on commitment seals, and I could have opened the record back when I was there. By the time COVID restrictions eased and I went back to access the record, I was told that it was lost.

Once I struck out on round two with the annoying New York State Supreme Court records people, I assumed that I would never know the circumstances that surrounded Elizabeth’s magical appearance in the 1940 Census at the Rockland Asylum.

But I was wrong.

The New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (https://nyspcc.org/) was a core source in solving the family history mystery (two newborns that wound up with the wrong parents) at the heart of Libby Copeland’s The Lost Family. It struck me that if things truly unraveled for my grandmother and her two sons, perhaps there might be some record of this with the Society. Perhaps someone lodged a complaint or a concern, and someone from the Society stopped by to investigate. Was there some record that I had yet to find that would provide some hint as to how or why Elizabeth was committed in 1938?

And it turns out there was.

The rest of the story is a long one, and at the risk of being a spoiler for those who might read the book, let me just say that it turned out that my grandfather Francesco and grandmother Elisabetta lived, unknown to anyone and institutionalized by the State of New York, for a long time. A very long time.

It strikes me that as unhelpful as the State of New York was in providing access to my grandparents’ mental health records, I am grateful that other records and archives existed that revealed their story. Without these records – and without the people who initially preserved them, the people who maintained them for a century, and the technologies that allowed these records to surface – the story of my grandparents would have been forever lost.

Except for the records and the archives.

——-

John Mancini is the author of a book documenting the search for his grandparents, Immigrant Secrets. Some of the original source documents for the book can be found on https://www.searchformygrandparents.com/. Coming next month — the Audible version!