Fathers and Baseball

On October 25, 2019, I finally made it. To my first World Series game. It was only 24,493 days after my father made it to his only World Series appearance. It took a while. As Terrence Mann said, “America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It's been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt, and erased again. But baseball has marked the time.” Yes, 24,493 days is a lot of “time marking.”

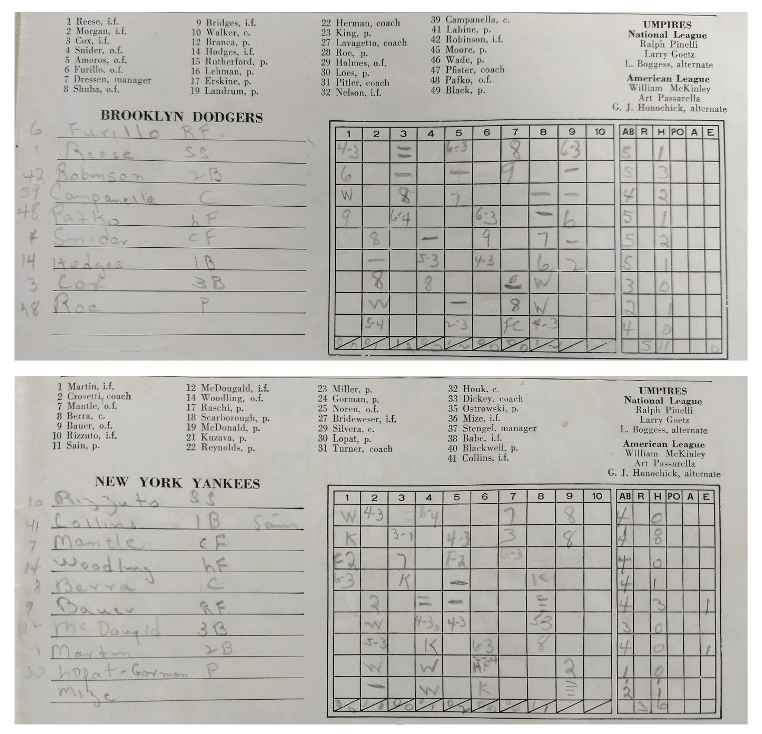

The program for my dad’s only World Series game -- game three of the 1952 World Series between the Yankees and Dodgers at Yankee Stadium -- has long had a framed place of honor in our home. Before I head to my first World Series game, I take the frame down off the wall, undo the clips on the glass frame, and leaf through the pages, looking for some sort of bizarre connection across the decades.

It is strange to hold this physical “thing” from 1952, directly connected to my father. I immediately notice the size of the scorecard -- it’s only 50 pages -- and the price -- 50 cents. Yes, time marches on.

I look online to find out how much the tickets were for the 1952 World Series, hoping that he had good seats. Seats in the lower deck for game 3 in 1952 were $6. Our seats for today are listed for $350 each, and they are selling for $2,500 in the secondary market. Which seems a lot, but speaking of the question of marking time, it’s been 31,431 days since the last World Series game in Washington, DC. On Oct. 5, 1933, the Washington Senators hosted the New York Giants in Game 3 of the World Series. The Senators won the game, 4-0, behind a five-hit shutout from Earl Whitehill. Ultimately, the Giants won the World Series in five games.

Leafing through the program, I am struck that almost every advertisement is by one of four sources: alcohol (Schenley Reserve, Chivas Regal, Park & Tilford Reserve, I.W. Harper, Seagrams), beer (Knickerbocker, Ballantine, Piel’s), cigars (Garcia y Vega, La Corona, Antonia y Cleopatra, Webster), and cigarettes (Lucky Strike, Old Gold, Chesterfield). I am particularly drawn to the cigarette ads: “L.S.M.F.T. - Lucky Strike Means Fine Tobacco,” “Where I come from, more and more folks say -- For a TREAT instead of a TREATMENT smoke Old Golds,” and “Nose, Throat, and Accessory Organs not Adversely Affected by Smoking Chesterfields.”

The short player biographies are amazingly familiar to me, even though all these players retired before I was of an age to pay attention. I suppose this is part of the curious generational connections that are unique to baseball, connections that are a mystery to the non-fan.

I start scrolling through the pictures of all 28 Dodgers and 27 Yankees listed in the program, all contemporaries of my father, born between 1918 and 1931, and the pictures strike a dissonant chord, a note that it takes me a few minutes to interpret, and then it dawns on me. Five years after Jackie Robinson broke the color line, only four of the Dodgers -- and NONE of the Yankees -- are African American. A little research, and I discover that it won’t be for another two and a half years -- April 14, 1955, 923 days hence -- that Elston Howard will appear in the Yankees lineup and break the color line for the sainted Yankees. Yet another reason to hate the Yankees.

I quickly Google these 55 players from the past and realize that like the players in the cornfield in Field of Dreams -- and for that matter, my father -- no matter how alive they may seem in my mind, they are indeed from the past. Despite how curiously alive the names seem, only two -- pitcher Carl Erskine and infielder Bob Morgan -- are in fact alive.

My father’s scorekeeping -- 24,493 days ago -- comes alive in my hands. I know all the names in the lineup for a game that occurred 24,493 days ago, even though I do not know the names of the people who live next door to us.

For the Dodgers, batting first, Carl Furillo (RF), followed by Pee Wee Reese (SS), Jackie Robinson (2B), Roy Campanella (C), Andy Pafko (LF), Duke Snider (CF), Gil Hodges (1B), Billy Cox (3B), and Preacher Roe (P). And for the Yankees, Phil Rizzuto (SS), Eddie Collins (1B), Mickey Mantle (CF), Gene Woodling (LF), Yogi Berra (C), Hank Bauer (RF), Gil McDougald (3B), Billy Martin (2B) and Eddie Lopat (P).

Strangely, for both the Dodgers and Yankees, my dad started the lineups up one line higher than he should have, which means that you need to jump one line down from each player’s name to find out what they actually did in the game. He used a very clean and straightforward scoring system, just recording the bare minimum of information for each at bat. A “W” for a walk. One, two, three, and four lines for a single, double, triple, and homerun. Just an “E” for an error and an “FC” for a fielder’s choice. Fly ball to LF, just a “7.” Groundout to short, just a simple “6-3.”

The Yankees scored first in the button of the 2nd. Hank Bauer walked and Billy Martin was intentionally walked to get to the pitcher, Eddie Lopat, who promptly singled for a 1-0 Yankees lead. The Dodgers tied it in the top of the 3rd with a double by Carol Furillo, a single by Pee Wee Reese to advance Furillo to 3rd, and a sacrifice fly by Jackie Robinson.

Billy Cox singled for the Dodgers in the top 5th, advanced on a sacrifice bunt by Preacher Roe, and scored on a single by Pee Wee Reese. Dodgers, 2-1. They made it 3-1 in the 7th on singles by Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella, and a sacrifice fly by Andy Pafko. Yogi Berra homered in the 8th to make it 3-2, making him 3 for 4 on the day (single, double, homer).

All of this is a weirdly crystal-clear communication from my father through the miracle of baseball scoring. I can “see” these plays unfold before my eyes just through his simple pencil notations from more than half a century ago. The Dodgers scored two in the top of the 9th to go ahead 5-2 (Reese and Robinson singles, a pair of stolen bases, and then a Yogi Berra passed ball to allow two runs). Johnny Sain pinch hit for Lopat in the bottom of the 9th and homered, accounting for the 3rd Yankee run in their eventual 5-3 loss.

How have all these oddly familiar names passed directly through the years from my father to me, familiar to the point that I somehow imagine that I saw these long-dead Dodgers and Yankees play? I realize it’s not just old film clips, run during the World Series and rain delays and the Ken Burns baseball special. It’s because my father talked about these players when I was growing up, talked about them as if they were family, talked about them as if he knew them, talked about them in the same way I talk to my family about Zimmerman and Max and Stras and Soto.

And yet beyond the simple fact of his parents’ names, his brother Vinnie, and a mysterious “Aunt Jennie,” in real life he never made any mention of his real family. Ever.

For more stories surrounding the mystery of my long-lost grandparents, click HERE.