An Awful Chapter in Virginia's Past

I recently attended a presentation by Greg Crawford at the VAGARA (Virginia Association of Government Archivists and Records Administrators) annual meeting that got me thinking about an aspect of records and archives and the recording of history that I had never considered before. Greg is the State Archivist and Director of #Government #Records Services, Library of Virginia.

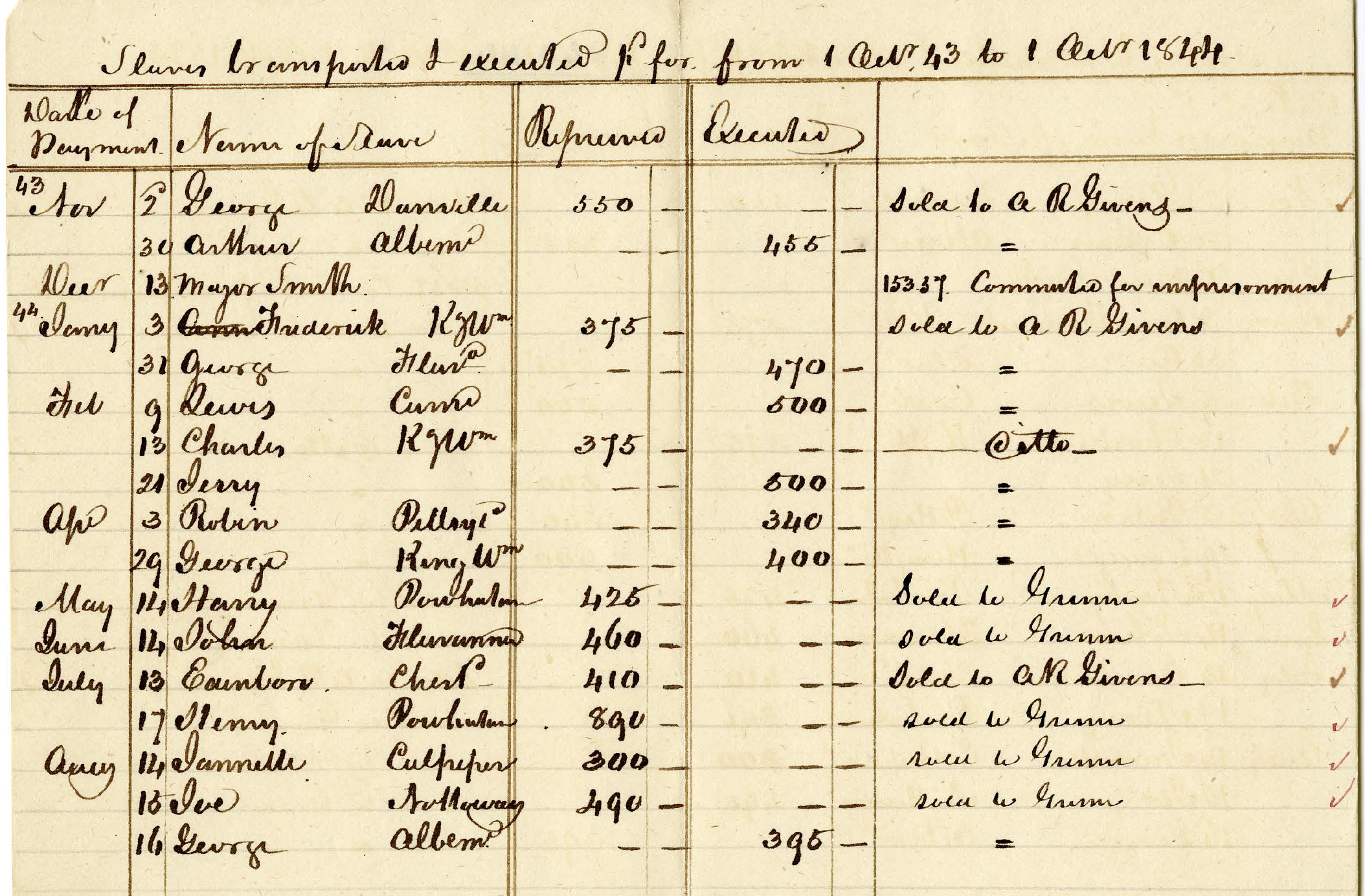

Greg shared this document. It tells an incredible and tragic story.

It is a “spreadsheet” of payments associated with incarcerated slaves “transported” or executed by the Commonwealth of Virginia from October 1843 to October 1844. The first column shows the date of the transaction . The second shows the first names of the incarcerated slaves and their county. The next column shows the income received by the Commonwealth when some of these poor souls were sold to new owners in the Deep South. The next column shows the slaves who were executed, and the amount of money the Commonwealth reimbursed the “property owner” for the loss of their property.

This was clearly a horrific — and profitable — business for the Commonwealth. And without this “spreadsheet,” evidence of this crime would have been lost to history. This record is fortunately now preserved for us to better understand and learn from the sins of the past. (Well, except for the history deniers who want to gloss over our past.)

But.

In addition to getting me thinking about a lot of uncomfortable history, this record also got me thinking about the question of what we preserve and why, and how this impacts the prism through which future generations will view the history we are creating every day.

I am afraid a record of a transaction like this would not have been considered in 1843 as anything unusual or meriting any particular attention or preservation. By modern records retention standards, it is likely that a financial record like this would have had a retention period of somewhere between three and ten years, and then would have been destroyed. It is just pure luck that it was preserved.

And without this record, this tragic history would never have come to light.

Maybe other people have thought of this tension between effective records retention — and disposition — and the potential gaps this might create as historians in 2203 look back at the actions we are taking in 2023. I’ve always thought about records retention and disposition as a critical component in recording who did what to whom and why. And it’s obviously a fool’s errand to save everything.

But what about the gaps that inevitably result when information that is viewed as "inconsequential" NOW doesn't make the cut as a record? How much information that might shed great insights 180 years from now is being discarded today? And MUST be destroyed if we are to keep our heads above water.

I know this is an inescapable records and archive tension that we just need to live with. But it still bugs me.

![11/52 - The [Altered] Photo Heard Round the World](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e078a4793d3ea1098311149/72ea19a7-5e2a-4006-85e0-5d66a6f52cd7/Screen+Shot+2024-03-15+at+3.14.00+PM.png)