8/52 - Immigrants. We Get the Job Done

Yes, this is an excerpt from a Hamilton lyric.

In a previous post (Number 5/52), I spoke about how my father and his brother eventually wound up in the apartment of a third deFabritus sibling, Dominick. Dominick initially came to the US at age 22 in 1914 aboard the Regina D’Italia. He had $28 in his pocket, and his point of reference in the US (in addition to his sisters Adrianna and Theresa who had arrived in 1904) was his half brother Michele, the earliest deFabritus arrival to the US (in 1903).

Dominick would return to Italy in 1920, marry Elisabetta Gelfu, and travel back to the US in 1920 in 3rd class on the RMS Olympic with his new bride, along with Douglas Fairbanks and his new wife Mary Pickford (in 1st class), wanabee stage performer Archie Leach/Cary Grant (in 2nd class) and my grandmother, another Elisabetta. Readers paying close attention will recall the reconstruction of this journey in Immigrant Secrets, so I won’t spend a lot of time on it.

By 1940, Dominick and Elizabeth were living on 27th Street in Manhattan with their three children, Marie Frances (b. 1921), Gloria (1922), and John (1924). My father and his brother entered into this mix sometime after the Census was taken.

Of course, we knew none of this until the past few years. My brother, my mom, and I were fortunate to track down the effervescent Marie Frances (Sinapi) in Staten Island in 2016, and she was quite the character (sadly, passed away last year). She immediately whisked us off to a local Italian restaurant that wasn’t even open for lunch, and persuaded them to open just for us. I wish I had recorded the conversation; she had so many nice things to say about my dad and his brother. At the time, I didn’t realize that my uncle was actually still alive, although institutionalized.

But all that’s a story for another day. The thing I really wanted to write about today is a bit of history I discovered about Frances’ father Dominick (my grandmother’s brother, for those who are following along at home) and his service in World War 1. And the reason for the title of this post.

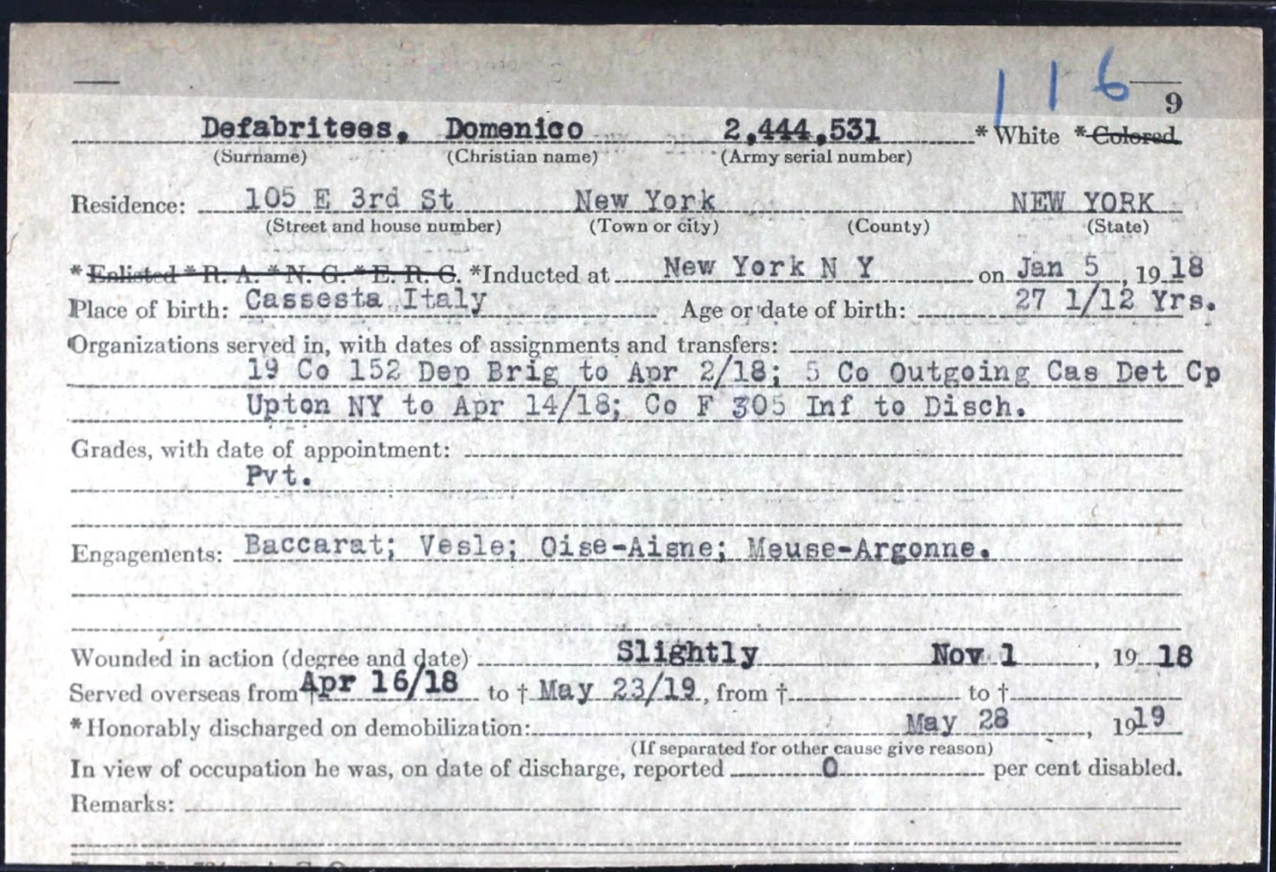

Dominick came to the US in 1914. It seems hard to believe, but by 1918 he was on his way BACK to Europe as a part of the 305th Infantry Regiment, Company F. There is an amazingly detailed book on the 305th in WW1 (available as a free download from the Library of Congress HERE - https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcmassbookdig.historyof305thin00tieb/?sp=1&st=grid). Any quotes that follow are drawn from that book.

For those a bit short on history, the Americans entered WW1 when everyone else concerned had been stretched to the point of breaking by years of trench warfare. The 305th was not all that different from the regiments quickly assembled after the U.S. declared war in 1917:

“It was a Wednesday afternoon, at 3 PM and raining like mad when our train pulled into a place called Camp Upton. They had a band of music at the station playing the Star Spangled Banner, to get us to feel like fighting. It did — the way they played it. A few roughnecks from the regulars received us. The Sergeant gave a command: ‘Column of twos. Forward. March.’ But we bums stood like a bunch of dopes, for we didn't know what a column of twos meant.”

One element of the 305th that WAS perhaps a bit different from others was the degree of diversity in its ranks, drawing extensively from fairly recent New York City immigrants: “...a surprising assortment of nationalities, whose names ran the gamut of the alphabet, backward and forward. It is said that a lieutenant, calling the roll of his company, happened to sneeze. Four men answered: ‘Here.’” Irvin Cobb offered this description in the Saturday Evening Post…

"I saw them when they first landed at Camp Upton, furtive, frightened, slow-footed, slack-shouldered, underfed, apprehensive — a huddle of unhappy aliens speaking in alien tongues, and knowing little of the cause for which they must fight, and possibly caring less.”

Even getting to Europe was not without its challenges. Company F was in a train accident on the way to meet their departure ship:

“There was a terrible rumble and a crash and a grinding and darkness; terrible moaning as someone crawled out from under the pile of seats, packs, rifles, glass and dirt, to strike a match. We were lying on the ceiling of the cars, gazing through the debris up toward the floor. Somebody chopped a hole through the floor, through which we clambered only to find the whole train in the same topsy-turvy condition. By the light of huge bonfires hastily kindled, the rescue work went on. Three of our good pals were killed and sixty others were so badly injured that they didn't come across with us.”

Company F was part of General Pershing’s First Army, which played a significant role in finally bringing World War 1 to a conclusion. The First Army spearheaded the successful American assault on the Hindenburg Line, a heavily fortified German defensive position. This breakthrough was a major turning point in the war, shattering German morale and demonstrating the increasing strength of the American forces. Following the Hindenburg Line victory, the First Army played a central role in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the largest operation on the Western Front. The Army's sustained attacks, despite heavy casualties, pushed German forces back towards their own territory, further weakening their resistance.

Company F arrived in Liverpool on April 28, 1918, crossed the English Channel at Calais, and then proceeded to make its way across France to the Eastern Front. It ultimately arrived in the Battle of the Argonne Forest in late September. “Many a poker game was broken up by stories the sergeants brought back from the front -- that a drive was about to start which would mean the end of the war, and that many an extra first-aid man would be on the job. Hurried letters were written to the folks at home. Vigorous preparation for the onslaught ensued, two extra bandoliers of ammunition, hand grenades, rifle grenades, and wire cutters were issued -- everything necessary to kill a man.”

An account from October 2 captures the intensity of the fighting.

At 3:30 we lined up…and started over the crest of the hill. We were at once under direct machine gun fire, the worst yet, and it seemed as if the air was so full of bullets that a man could not move without being hit. A man standing upright would have been riddled from head to foot….The only order that could be heard was ‘Forward,’ and Company F was game. It was awful. The poor boys were getting slaughtered as fast as sheep could go up a plank. No one could ever describe the horror of it. The screams of the wounded were terrible, but we stuck to it.

By the beginning of November, it was clear that the will of the Germans to continue to fight was fading.

There was wide-open talk of an armistice. Everyone thought he had fought his last fight, that in the general order of things, before our depleted ranks could get into the line again, either the war would be over or the opposing armies would have dug in for the winter. It was growing too cold and wet for further operations; the men couldn’t live through many more nights in the open.

But the war was not quite over. Dominick was wounded on November 1 in the Battle of the Meuse, a mere ten days before the Armistice.

...the Second Battalion was reduced to about half of its morning strength by a scorching fire, both shell and machine gun, poured down upon their heads from the high ground at Champigneulle.

And the war to end all wars came to an end. Less than two years after he returned to the US, Dominick returned to Europe, and brought home a new wife. And my grandmother.

----

This is part of a series of posts designed to keep me busy and off the street. Hopefully some of these musings will contribute to a successor to Immigrant Secrets (https://www.amazon.com/Immigrant-Secrets-Search-My-Grandparents/dp/B0B45GTTPP).

You can get the posts directly HERE (https://www.searchformygrandparents.com/subscribe) or use the subscribe button on this page (https://authory.com/johnmancini).