1945 – The sad endgame for John Oliver Manson

Note: I have written a great deal about the search for my long-lost paternal grandparents, the sad Elisabetta DeFabritus and Francesco Mancini, and eventually published a book called Immigrant Secrets (https://www.amazon.com/Immigrant-Secrets-Search-My-Grandparents/dp/B0BGMHQ6WL) about the search.

In a series of new posts, I’m going to start to document another unusual family character, my maternal grandfather, John Oliver Manson. I will likely hop around a bit as I do the research, so I’ll put a date stamp in the titles so those keeping score at home can follow the timeline. Previously published posts are listed at the end of this one.

As noted previously, my mother’s father, John Oliver Manson, was a bit of a character. Thrice married, a sea captain, a silver miner, and famous Miami boat racer were among his many titles. He wandered – and wandered…and wandered. He was an absent father for most of his life, often leaving my immigrant Irish grandmother to fend for herself.

Unknown to me, before I began my own family history searching, my mother – at a similar age as I am now – had done some searching of her own. Of course, thirty years ago – pre-internet, pre-Ancestry – this was quite a challenge. When I started to research John Oliver/Otto Johan, one of the things I did first was to create a timeline for his life to chronicle his many wanderings. Until I came across this sheet of paper in her things, little did I know that my mother had taken the exact same approach to begin to better understand her father.

Much of this information came from a request she made for his military records. It is somewhat astonishing that the file was so large, given that his full WW1 military history lasted all of 10 months before he wound up in the hospital.

One of the reasons that the file was so large was that this very brief service history set in motion a long chain of VA hospital check-ins and VA pension requests over the years, all the way up to his death in 1945. A 1941 VA record provides this medical history.

Accidentally shot, age 18, while in South Africa (left side of chest). In 1897 in a Rio Janiero Hospital for yellow fever. Malaria several times, also yellow jaundice. In Key West Hospital in 1930 for cysts of spine. Ruptured gastric ulcers in the fall or 1936 or 1937, surgery in private hospital, and admitted at Bay Pines, Florida, to recuperate. Last hospitalized at Bay Pines December 1940 for high blood pressure. Uses no drugs nor alcoholics. Smokes about 10 cigarettes a day. Operated for ruptured gastric ulcers 1936 or 1937.

Certainly, a lot to unpack here, not the least of which are that gunshot wound and the persistent malaria. Either my grandfather had a LOT of medical issues, or thought he did, or maybe a bit of both.

According to the Mayo Clinic, malaria deaths are usually related to one or more serious complications, including:

Cerebral malaria. If parasite-filled blood cells block small blood vessels to your brain (cerebral malaria), swelling of your brain or brain damage may occur. Cerebral malaria may cause seizures and coma.

Breathing problems. Accumulated fluid in your lungs (pulmonary edema) can make it difficult to breathe.

Organ failure. Malaria can damage the kidneys or liver or cause the spleen to rupture. Any of these conditions can be life-threatening.

Anemia. Malaria may result in not having enough red blood cells for an adequate supply of oxygen to your body's tissues (anemia).

Low blood sugar. Severe forms of malaria can cause low blood sugar (hypoglycemia), as can quinine — a common medication used to combat malaria. Very low blood sugar can result in coma or death.

For purposes of this post, though, I want to focus on the last few months of his life.

As readers of Immigrant Secrets know, my father kept a lot of his family history to himself. My mother has been a bit more forthcoming, particularly about my grandmother Sarah, but she did leave a few holes in her father’s history, as we discovered when looked through the military records she requested.

By 1943, my grandfather had “settled” in Nevada, likely not the best of destinations for someone with a known propensity for risk. He divorced my grandmother in November 1943 and married his third wife Alice three days later, whom my mom notes was identified as his “sister” prior to that. Immediately after the divorce decree, my grandmother’s portion of John Oliver’s military pension was terminated, likely setting off a financial scramble back in New York City for my grandmother.

By early 1945, John Oliver was somehow back in Florida – in Orlando and admitted to the VA Hospital on March 8 for: 1) bronchial asthma; and 2) angina pectoris. Whether his Nevada sister/wife travelled with him to Florida is unknown. “Flat feet” show up in the list of ailments; the record says they were “not found,” which sounds like a strange given that I would have assumed this has a relatively straightforward binary condition. John Oliver was in the hospital almost three weeks and treated for a variety of ailments and released on March 27 because he had reached the “maximum hospital benefit.”

By May 11, John Oliver was back in Nevada in a different VA hospital. One thing that strikes me as amazing about my grandfather’s life is that he spent a LOT of time going back and forth to the west coast at a time when travel was certainly difficult. The list of ailments is like those from the Orlando stay (albeit without the missing flat feet), although his angina had worsened from Class 2 in Orlando (“Angina causes slight limitation of ordinary activity. It occurs when walking rapidly, uphill, or >2 blocks; climbing >1 flight of stairs; or with emotional stress”) to Class 4 (“Angina occurs with any physical activity and may occur at rest.” He was in the hospital three weeks and discharged on May 31.

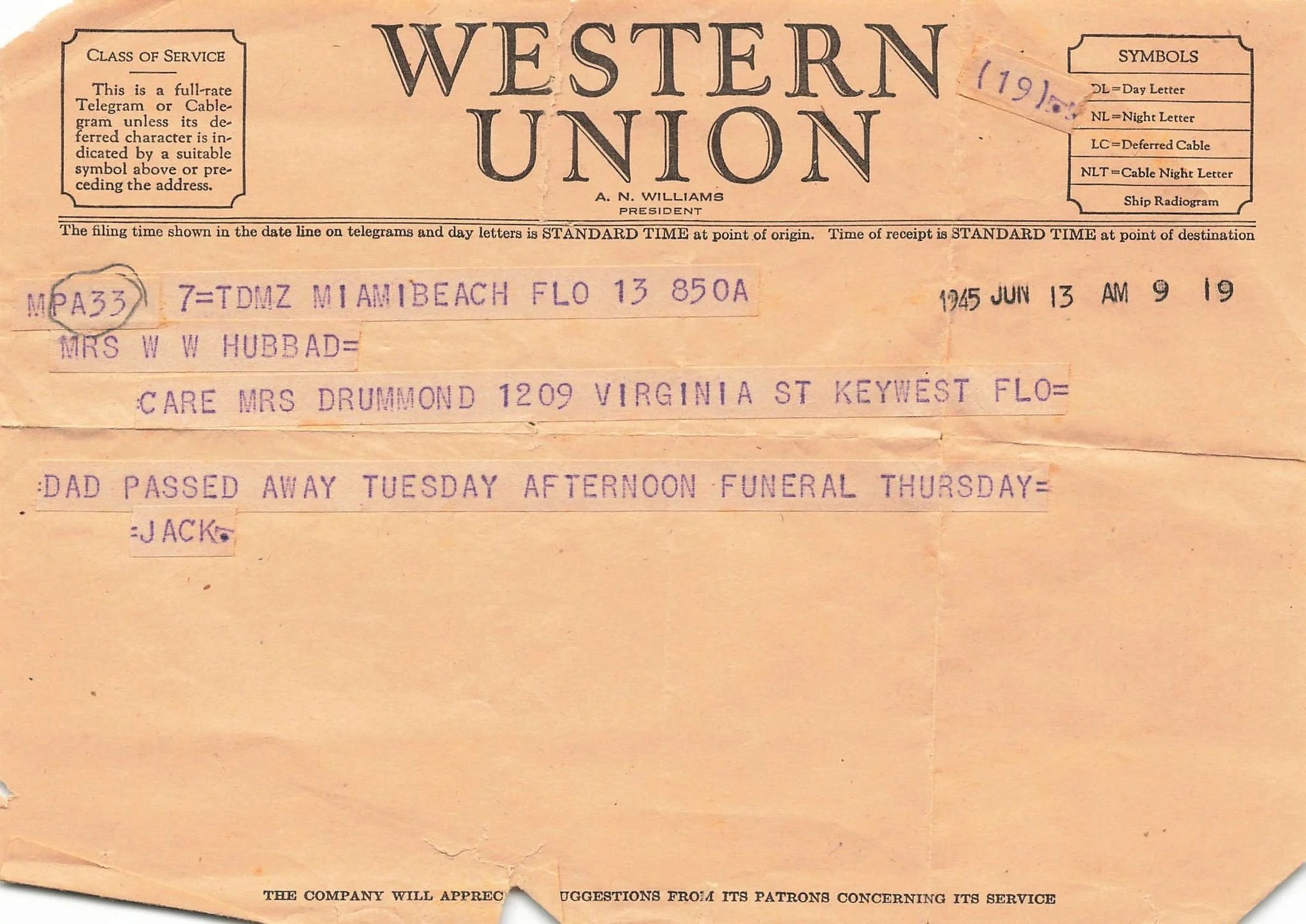

By June 12, John Oliver Manson was dead. Just a few days past his 65th birthday.

My grandfather, while a rascal, was apparently a person of some note; all the local newspapers covered his death in the news sections (in addition to the usual paid obituaries).

The family lore about all of this was minimal. I think if we paid attention to the stories at all, we have just assumed given his heart ailment that he died of a heart attack.

Except he didn’t.

At some point, my mother passed along all the military records to my brother and me, including his death certificate.

Now of course, what anyone looking at this copy of the record would notice first is that she made a curious redaction under “immediate cause of death.” The paper record my mother sent us had her own personal redaction – a dark magic marker line through the immediate cause of death.

I guess I understand her reluctance to share this with us – to spare us from this -- although I don’t think she gave us credit for the smarts to just hold the magic-markered paper up to the light and see the original typing. Or that we would ultimately get a copy of the original from Ancestry. Electrons never die.

As I think about my mother – she’s still kicking at 91, although not in the best of health – one of the things I’ve realized is that she’ll always be the child of that absent father. As a result, she has a tough crust, does not suffer fools gladly, notices everything, and often has her guard up. Like many of her generation, she never talked about things that were embarrassing or unpleasant or “family business” or might show weakness. I think she spent many years sustaining the hard shell that she created as a 13-year-old girl to protect herself from the memory of not only an absent father, but one who ultimately took his own life.

Just one more entry in our sad list of family secrets.

Other posts that might be of interest…

A snapshot of family stories from just one New York State Asylum

1880 - Wait. My Grandfather Wasn’t Born in Australia?

1913 - My Grandfather and the Mystery of the Columbus Bones

1917 – Father and Son Miami-to-Key-West Race Winners – Or Were They?